Parent Category:

Reward comes when preparation meets opportunity

Introduction

In humans and canines, body structure can be related to overall health. If a human has legs that are bowed out or bowed inward or if the spine is curved, that person is likely to suffer from pain and other health problems. The same can be true for canines and their structure even though there are structural differences between the species. Regardless of one’s breed, correct structure can be related to correct movement and good health.

Dog experts consider breed standards the single best guide to understanding what is correct structure and correct movement. Standards are designed to reflect not only a breed’s appearance and architecture but also their purpose, function and temperament. Breed standards are not checkbox lists of requirements, but rather a description, giving a detailed "word picture" of the ideal dog. They are written statements that describe the desirable and undesirable attributes of each breed. Due to the great variability between breeds, there is no one standard that fits all breeds. What is good conformation for a terrier may not be good conformation for a working dog.

Differences occur between breed standards can be related to the variations found in a breed’s function and purpose. For example, those that herd and hunt must travel over long distances. Their length of leg will not be the same as those whose function and purpose requires speed. While there are many differences between breeds and individual dogs, there are also common factors that link them together. For example, all breeds have an excellent sense of smell and hearing and have the same number of bones which are tied together by the same number of muscles, tendons and ligaments. The ways in which they are connected and positioned determines the architecture of a breed. Factors that separate one breed from another are found in their country of origin, history, and purposes for which the breed was developed. Collectively these factors influence the size, shape, weight, length of bone, coat and color of a breed.

Structure

Our knowledge of dog anatomy helps to explain why breeds are known for their special and unique traits and colors. While there are many structural variations between breeds, common to all is the desire for correct balance and angulation, which are two of the fundamental concepts used when evaluating dogs.

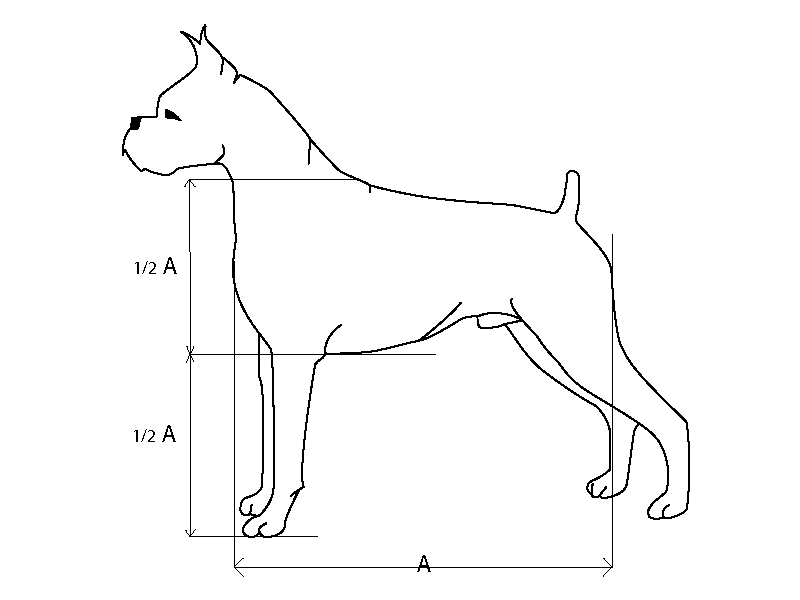

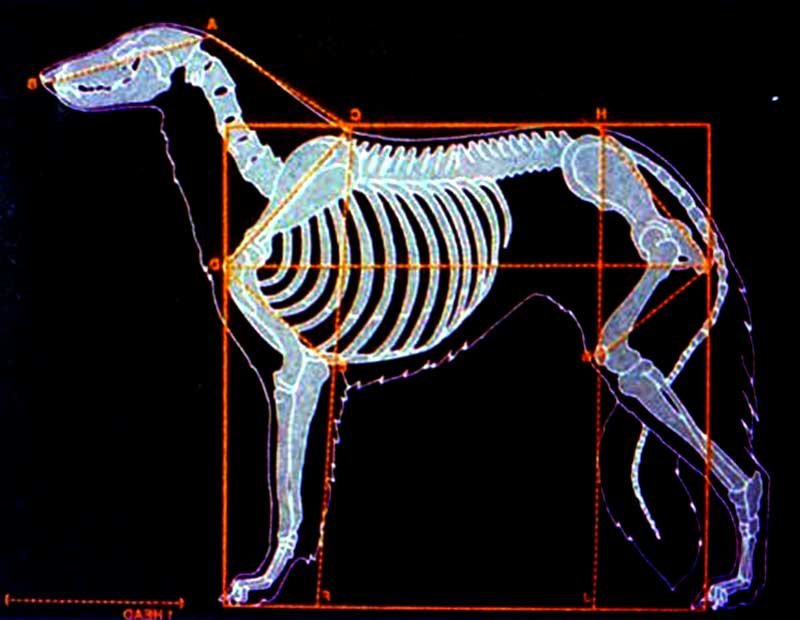

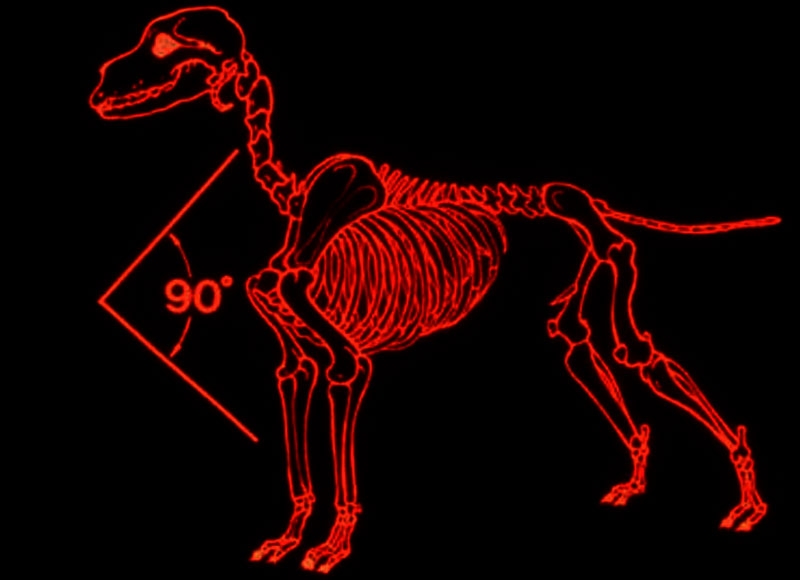

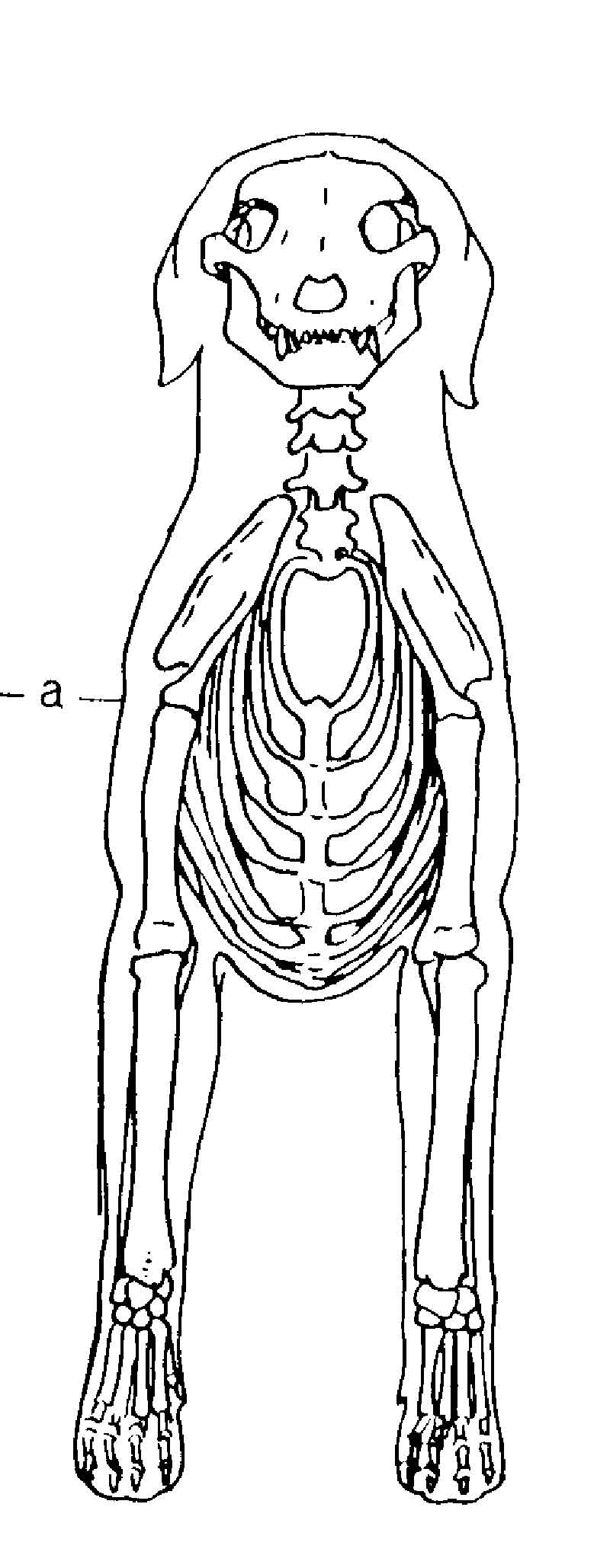

Balance is a term associated with the appearance and structure of a dog’s body. The term refers to the symmetrical proportion of the parts in relation to each other. It also means the relative proportion of the parts to each other. Angulation is another term associated with a dog’s body. It refers mainly to the bones of the front and rear assemblies and their angles at the hip and shoulder joints. When evaluating structure, judges look for the same angles at the shoulder and hip joints. Dogs with good balance and angulation as seen in figure 1 and 2 will have a smoother stride then those who lack balance and have fewer angulations.

Figure 1. Balance & Angulation

Figure 2. Balance & Angulation

Head

The over-all shape of the head, combined with the size and shape of the ears and eyes, coupled with the planes of the head, are traits that give a breed its unique appearance. For these reasons the head is considered the hallmark of a breed. It is one of the most distinguishing parts of a breed and it influences a dog’s overall appearance which is called breed type. The term "breed type" includes the silhouette, head, body proportions, coat and color. By definition "breed type" means that a dog looks like its breed. Some dogs will come closer to their breed standard than others. This explains why there are many variations in "type" within a breed. Often times when two or more breeders meet in discussion the following phrase will be heard. "We have two types in our breed; one type is used for obedience and another type for conformation". This is an incorrect use of the term "type", because by definition it means the dog looks like its breed. Thus, regardless of their faults, every breed will have only one "type", but they all will have many variations in "type".

Body

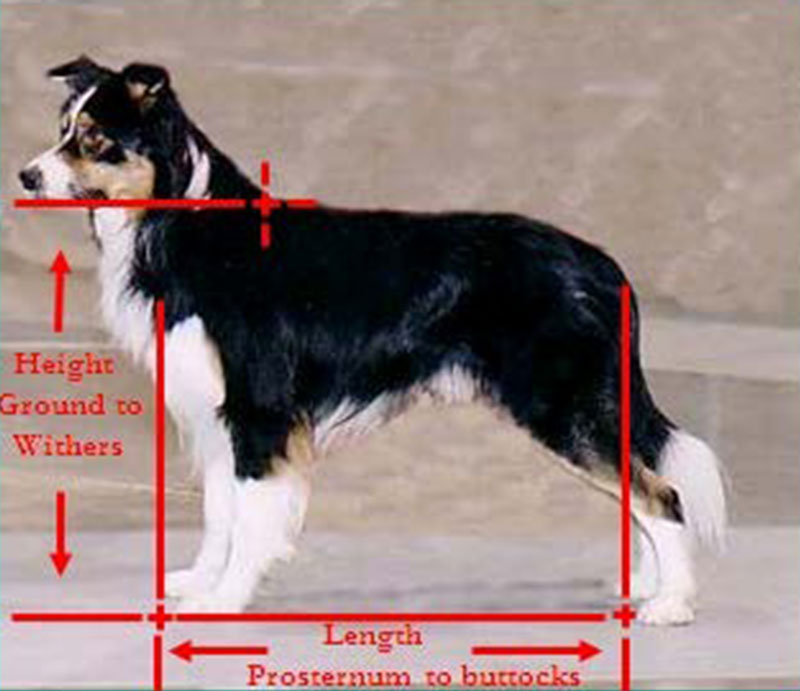

Breed standards are used to describe the architecture of a breed’s body proportions, size and shape. Most are described as either square, nearly square, long or rectangular. The breed’s ideal body size (height and length) can be found in the breed standard. Height is generally measured the same way in all breeds unless otherwise stated in the standard. For most, height is measured from the withers to the ground. Some standards are more specific about height. The terminology used in the Brittany standard calls for the height at the elbow to be approximately equal to the distance from the elbows to the withers.

Body length is not measured the same in all breeds and unless specified in the standard, length is measured from the point of the fore chest to the point of the rump. Here again there are breed differences as noted in a few examples. For example, the Wire Fox Terrier and Belgian Tervuren breeds measure the length of body from the shoulder point to the buttocks. The Canaan dog standard measures length from the point of the withers to the base of the tail. For the Cavalier King Charles Spaniel, length is measured from the point of the shoulder to the point of the buttocks. For the Akita it is from the point to the sternum of the point of the buttocks. For the German Shepherd Dog it is measured from the point of the prosternum to the rear edge of the pelvis or ischial tuberosity. For the Irish Red and White Setters, length is measured from the point of the shoulder to the base of the tail.

Body Shape

The standard for the Boxer describes the body as being square as pictured in Figure 3

Figure 3. A square body

Figure 4 illustrates another breed whose standard describes the body as nearly square body.

Figure 4. A nearly square body

These two illustrations highlight the subtle differences between a square and nearly square body. Thus, it is not uncommon to read breed standards that describe the measurement of length and height in different ways. Some breed standards describe length to height as a ratio. For example, the Border Collie standard describes the body proportion as a ratio as 10:9 (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Border Collie

The Doberman Pinscher standard body proportions are described (length to height) as 7:6. The German Shepherd breed standard describes body proportions as a dog that is longer than tall, with the most desirable proportion as 10:8.5.

The American Kennel Club allows breeds that have a disqualification for size or weight if stated in their breed standard to be measured or weighted in the show ring. Breed standards that do not provide statements for a disqualification for size or weight must be measured or weighted outside the ring.

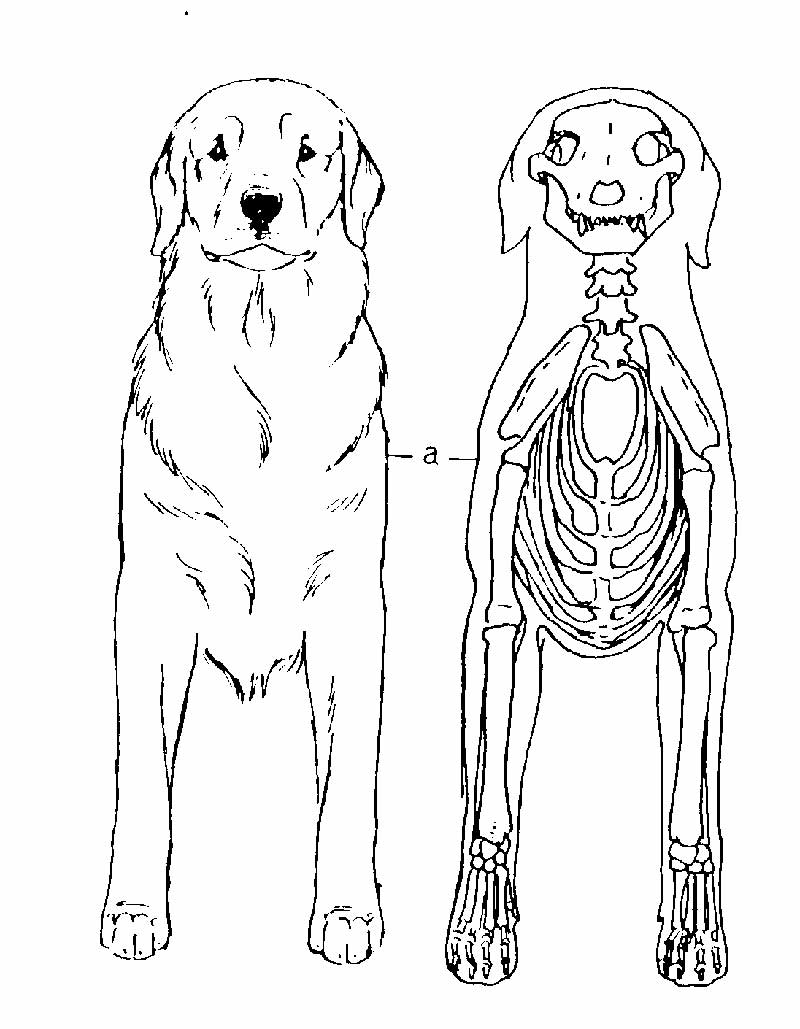

Front Assembly

The dog’s front assembly begins with the top of the shoulder blade which is called the withers. The front assembly includes the forearm, front legs, pasterns and feet. This series of bones are important because the front assembly carries sixty percent of the dog’s body weight and is only attached to the body by muscles, tendons and ligaments. The front assembly only includes a large number of moving parts. When standing still the front legs should appear as two straight columns of support from the hip joint or shoulder to the ground. This does not mean perpendicular, but a straight line from the shoulder or hip to the pad. The front legs should appear as two straight columns of support as illustrated in the Figure 6 and 7.

Figure 6. Straight line - shoulder to pad *

Figure 7. Straight line – shoulder to pad

Any deviation from the single column of support is considered a fault. This means that the elbows should not bow out and the feet should not toe in or out.

Lay-Back and Lay-In

Shoulder Lay-back and Shoulder Lay-in are two important elements of canine structure that influence movement. Unfortunately, the importance of the shoulder blades and how they are positioned is a subject not well understood by many newcomers. The term "lay-back" of shoulders means the tilt of the shoulder blades toward the back end or rump of the dog. Shoulders that are "laid-back" influence the dog’s potential to extend its front legs forward. The length of the upper arm or scapula and the degree of lay - back of the shoulder blades together influence the length of reach of the front feet when a dog is in motion. Most experts believe that the ideal shoulders should have an upper arm that is equal in length to the shoulder blade as seen in Figure 8 and 9.

Figure 8. Shoulder Blade = Upper Arm

Figure 9. Shoulders Lay-In *

The second term related to the shoulder blades is called the "lay-in" of the shoulder blades. This phrase means the tilt of the shoulder blades toward each other (Figure 9). The "Lay-in" of the shoulder blades tends to influence how the dog will put its front feet on the ground when in motion. As speed increases from a walk to a trot, the feet tend to move toward a center line in order to maintain balance. Breeds with shoulder blades that are not "layed-in" (tilted) toward the spinal column generally do not move toward a center line or single track.

A good example is the Bull Dog which has a four-tracking gait and the Corgi which has a two- tracking gait. Both breeds have shoulder blades that are more upright with shoulders blades that do not tilt inward toward the spinal column.

Topline

The topline is formed by the withers, back, loin and croup. This is the area from the base of the neck to the base of the tail. In most breeds the preferred topline is level, meaning that this area should be flat and strong. Level does not necessarily mean parallel to the ground. There are exceptions to breeds with level top lines. Some breed standards describe an arched topline such as the Whippet and Greyhound.

Rear

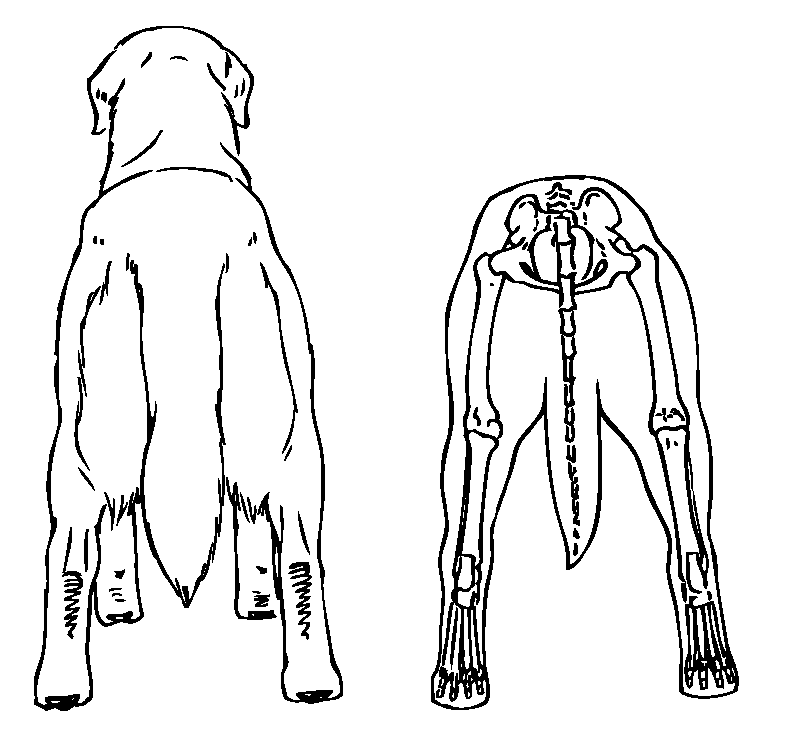

The rear assembly is another important part of dog anatomy. It involves the vital hip joint which connects the femur to the tibia and fibula at the knee joint. It gives the dog forward thrust and drive. When in motion the entire rear leg assembly should extend and flex through the hock to drive the dog forward. This end of the dog is less fragile than the front assembly because the rear assembly is attached to the body by two hip sockets which hold the rear assembly together; for this reason it is less likely to be affected by environmental and management problems during development. When a judge views a dog from behind they are looking to see if the rear hocks appear as two straight columns of support that are parallel to each other and set just slightly outside the hip sockets as seen in Figure 10 and 11.

Figure 10. Parallel

Figure 11 Underneath *

Cowhocks are undesirable in all breeds (Figure 12). They are weak and greatly impair efficiency and power of movement. Cowhocks cause rear pasterns to turn inward toward one another. This fault causes the stifle to turn out and the feed to toe out

Figure 12. Cowhocks

Unfortunately not all of the virtues and faults can be seen when dogs are standing. This is why it is necessary to see them in motion and at different speeds. Evaluations in the show ring include three basic forms of examination - standing and the individual examination , side-gait, and observing movement from the front and rear.

Part II will discuss many of the faults and virtues of structure when dogs are in motion and at different speeds.

After reading Part I and Part II the reader will have a better appreciation for the importance of good structure standing and in motion.

Note: * Illustrations by Marchia R. Schlehr

References:

Battaglia, Carmen, 2014. "Do you see what I see?" Canine Chronicle, April pp. 108. Battaglia, Carmen, 2008. "More than meets the eye" Canine Chronicle, Ocala, Fl., pp. 300, 302

Brackett, Lloyd, and Hartwell, 1965. Laurence A., "The Dog in Motion", Dog World Magazine, (USA) August 1961- October 1965

Elliot, Rachel Page, 2001. Dog steps, A New Look, Third Edition, Doral Publishing, Sun City, Arizona, pg. 68 -73

Gilbert, Edward M., & Brown, Thelma R., 1995. Structure and Terminology, Howell Book House NY.

Jenkins, Farish A., Jr. "The Movement of the Shoulder in the Claviculate and Aclaviculate Mammals", Department of Biology, Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard university, Cambridge, MA

Lyon, McDowell. 1950. Dog in Action, Howell Book House, NY, NY.

Gilbert, E, and Gilbert, P. 2013. Encyclopedia of K-9 Terminology. Dogwise Publications, Wenatchee, WA.

Jones, J, Tucker, T., Tan, J., Pierce, B., Foxworth, J, Long, B., Harper, T., Morens, D. 2013. "Improving understanding of early behavioral indicators of lumbosacral disease in working dogs using 3D visualization of skeletal movement during working task: Feasibility study", J. Beh., 8, pp. 309-315.

About the Author

Carmen L Battaglia holds a Ph.D. and Masters Degree from Florida State University. As an AKC judge, researcher and writer, he has been a leader in promotion of breeding better dogs and has written many articles and several books.Dr. Battaglia is also a popular TV and radio talk show speaker. His seminars on breeding dogs, selecting sires and choosing puppies have been well received by the breed clubs all over the country.